There was yet another piece in the New York Times last week about the disintermediation of established businesses as a result of our new, networked world. In this case, it was about how new map mash-ups are growing in popularity, to the chagrin of many professional cartographers. Here’s an excerpt:

With the help of simple tools introduced by Internet companies recently, millions of people are trying their hand at cartography, drawing on digital maps and annotating them with text, images, sound and videos.

In the process, they are reshaping the world of map-making and collectively creating a new kind of atlas that is likely to be both richer and messier than any other.

They are also turning the Web into a medium where maps will play a more central role in how information is organized and found.

Initially, I thought this article was further proof that networks automatically disintermediate. It’s just their nature. They cut out that faceless “middleman,” whether this “man” is a travel agent, a realtor, or — in the case of Wikipedia — a traditional encyclopedia editor. But then I heard a story that showed me how networks can cut both ways.

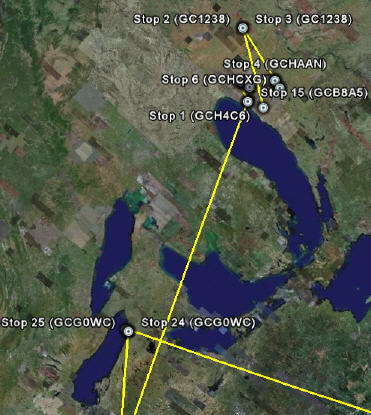

But first, a word about how place, as defined as our physical world, has always been subjective — that mash-ups are simply expressing this reality in another demonstration of The Long Tail. The above example from Google Earth is the path that a friend’s Travel Bug (lovingly named Tatoo Bug) took as it passed through Midwestern geocaches. This portion was the first leg in a worldwide, 15,951-mile trip that he and other enthusiasts continue to follow on the dedicated Geocaching site.

Just as blogging has shown what happens when you remove the high cost of entry to publishing, these new rich, personalized maps are what you get when you hand mapping tools to the masses. Think about what maps have been in recent history. And I define recent history as the time since researching and printing maps was only available to the chosen few.

When I was a child, living in the hinterlands of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (also known at “The U.P.”), I was surrounded by towns that were too small for most maps to even acknowledge.

To cartographers, they didn’t exist. The commercial effects were devastating.Â

Smack in the middle of a breathtakingly beautiful part of the country, with much to offer visitors, these tiny hamlets withered on the vine because tourists drove right past. These towns were achingly close to the tourist dollars they needed to survive. In some cases they were separated from major U.P. roads by nothing more than a stand of pine trees. So close and yet so far away.

That is all changing.

I’m a rock climbing enthusiast. The last time I climbed at Devil’s Lake, a spectacular set of quartzite climbing faces, I and my fellow climbers found the right place to set our gear based on an old, dog-eared book. The book was far from current, but it was the best we had. I’m expecting, within the year, to make my selection based on one or more Google Map mash-ups, enhanced with Flickr.com photos and user-generated raves, rants and warnings. My guide book will stay on the shelf, more a relic than reference.

And who knows? Maybe, armed with more personal — and personalized — knowledge of the area around Devil’s Lake, I’ll discover an ideal place to eat. One that I didn’t even know existed. A new perspective will reveal a physical world I didn’t realize was right there all the time.

Networks Can Intermediate Too

Is it inevitable that a networked world eliminates the middleman, shifting from an objective, imposed experience to a more subjective one? I thought so.

But on the same day that I read that Times article, I heard a wonderful NPR podcast. It was one of a series of programs called RadioLab, and this episode was about time. The program reminded me that there was an era in this county when small communities like my hometown had a very personal — and personalized — view of time. Up until about 200 years ago, these places had no official “time.” Noon was simply when the sun was directly overhead. You set your watch to that moment, and that was good enough.

Back then you could walk into a room and ask for the time, and get as many different answers as there were people answering. Some would even, quite sincerely, answer with something like “It’s nearly time for me to harvest the corn.” Because what was time, after all, but something you experienced subjectively?

One day that all changed, and everyone followed the same timeclock.

And the intermediary that created this change? None other than a network: The railroad.

With much at stake for both the train and the towns along its path, someone had to agree to exactly when the 12:07 train would pull up to the stop. The network wiped away all personal “maps” of time and replaced them with one that was objective and unyielding.

All of this is a reminder to me that two of the most agree-upon truths — Time and Space — which keep us moored to this harbor called Reality, are more open to interpretation that we would care to admit.

We all know that retail’s mantra and battle cry is Location, Location, Location. But the spread of map mash-ups helps us realize that what makes a location good is in the eye of the beholder. Take it from me: If what you want is a really good smelt fry, I know a place in Rapid River, Michigan that is worth seeking out.