Solving complex business problems “ain’t always rocket surgery,” to cite a colloquialism I just discovered. It often boils down to a little bar and a big bar.

As an outsider, I have the luxury of both working with data scientists and in gentle opposition. The first part is easy. Data scientists work with my clients’ data daily, and have produced elaborate models to help make things more understandable.

But I also work in gentle opposition. To quote best-selling author and distinguished professor of economics (and fellow “outsider”) Steve Levitt, it’s all in the incentives. He’s excerpted immediately below from one of his People I (Mostly) Admire podcast episodes. You can listen to this one-minute audio clip by clicking the player, or read on … the transcript immediately follows it.

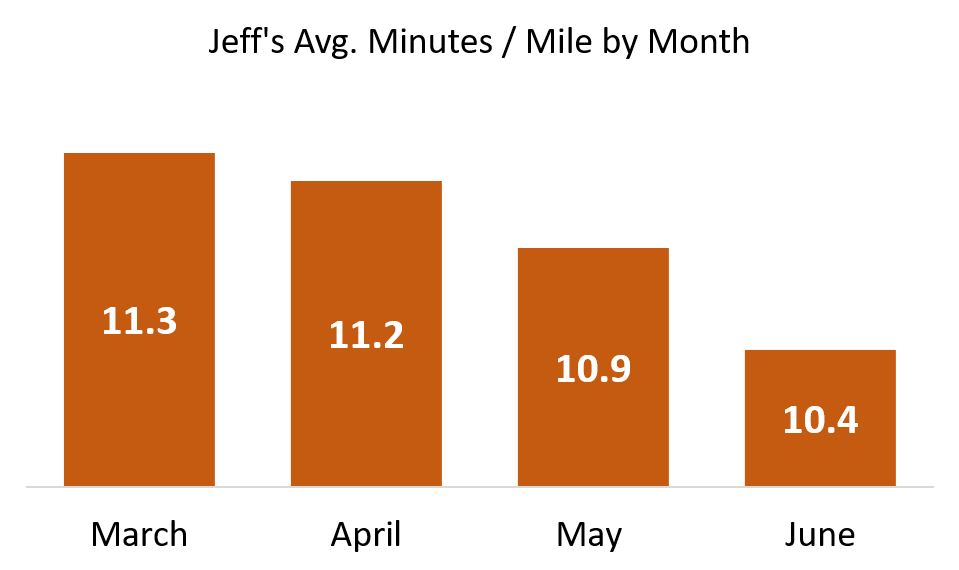

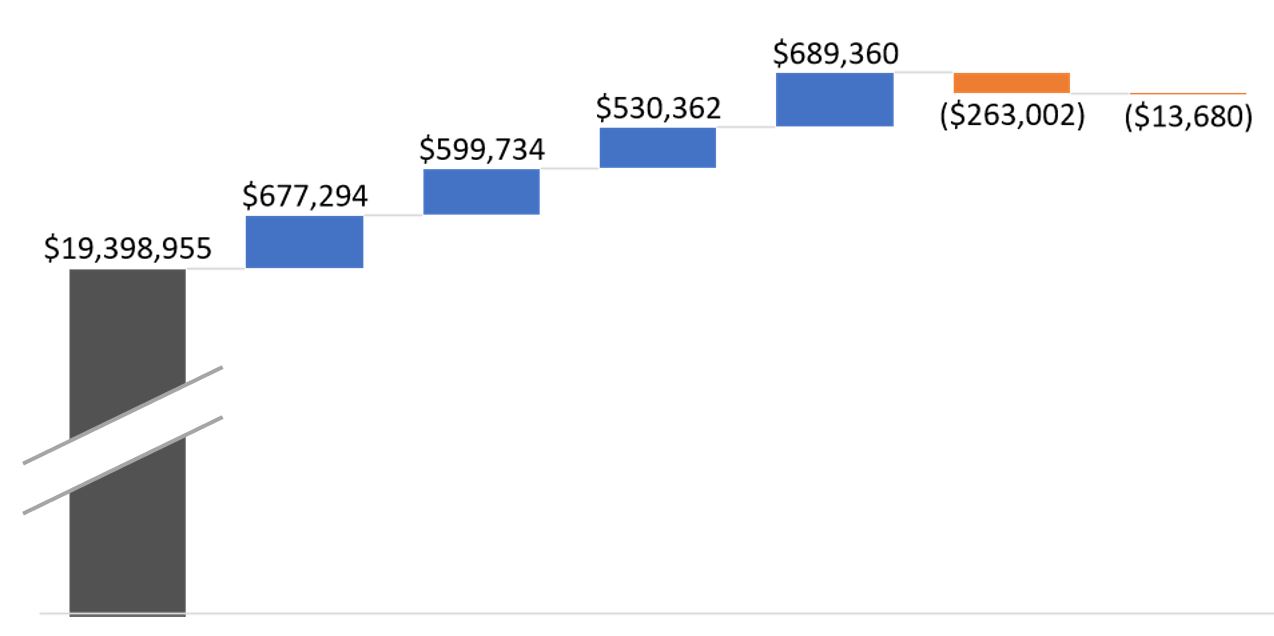

Little Bar / Big Bar

When I work with firms that have data scientists, what I find almost uniformly is that they operate in an incredibly complex space. They’re very concerned with technicalities, with techniques, with things being hard. And I think the answers are often very simple. So I try to always do simple things, and try to relate them in very basic ways. Like, my favorite kind of graphs are Big Bar / Little Bars graphs.

They’re graphs that have one really little bar … and one really big bar, and those are the kind of graphs that I show to CEOs if I’m trying to convince them of something. And the CEOs say to me, ‘Wow, that makes sense to me. I don’t understand how you take the same data that my data science team has and I never understand anything they’re saying.’

So, you might say ‘The answer is to do things really simply,’ but I think it’s more complicated when you think of incentives. Because much of the power that comes to data scientists in firms and organizations is because they are completely and totally inscrutable. And the other people have no idea what they’re doing. And by having a set of skills that no one else has, you can wield power because no one understands why you’re doing it. You have a very special talent. And so, I have the luxury of being an outsider.

Steve Levitt, “I’m Not as Childlike as I’d Like to Be” | People I Mostly Admire Bonus Episode

Wow! Can I relate. I hear this frustration when I talk to the leadership within my clients. Which is why I have espoused simplicity in everything I report, and have for years.

Of Oracles and Job Security

At the end of a talk I gave in 2018 about experience optimization, I urged the audience to think of themselves as modern day oracles. But instead of the literal magic tricks that the Greek vestal virgins employed to keep their jobs, we only have our science to keep us regarded as useful and legitimate.

Scrupulous science.

Many data scientists stop there. They generate reports using the latest and greatest methods, but when the output is shared, business leaders too often have no clue what the data is telling them.

That quote I shared with you from Steve Levitt was in response to a question about the future of data science as a profession. If you are a data scientist, consider this advice: Spend more time listening to your employer about the problems dogging them. And if you’re one of those employers, you cannot go wrong by hiring, when appropriate, someone outside of the data scientist industrial complex to whip up the bars!

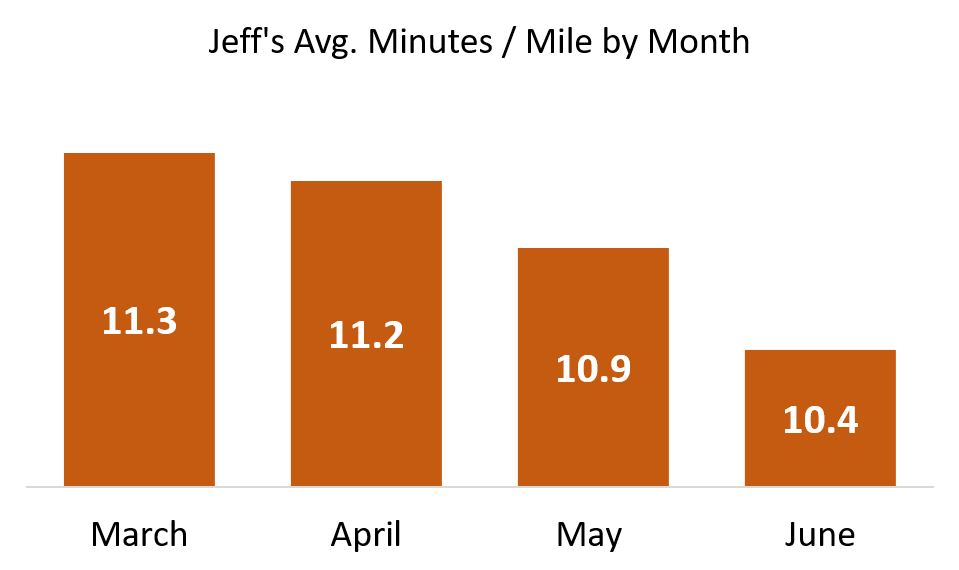

What does this chart tell us? Quite a bit.

What does this chart tell us? Quite a bit.