A few days ago a team crossed the finish line in a race to develop the best algorithm for the Netflix recommendation engine. It wasn’t easy. It turns out that the type of business logic once carried exclusively between the ears of a good video rental clerk is hard to automate. Netflix decided they needed help. They placed a price on improving suggestion results: One million dollars for a 10% or better improvement.

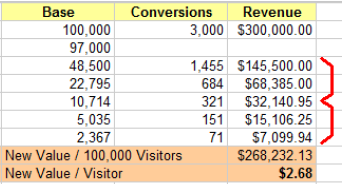

Teams around the world got to work. It took them three years to reach the 10% milestone. And 30 days after one team did, the best results over that threshold took the prize. Here’s the leaderboad.

We can learn from these teams’ struggles. The leaders who were interviewed all agree they couldn’t have done it without an interdisciplinary approach, tight collaboration and a willingness to be wildly creative. According to a piece in the New York Times, “the formula for success was to bring together people with complementary skills and combine different methods of problem-solving.”

In the physical world, we know that the more hands you have to lift something, the heavier an object you can lift. But most of us in our digital, information age careers, have a difficult time imagining that this synergy is possible when the heavy lifting is computational. We need to think again.

Quoted in the Times piece, David Weiss, a member of one of the teams competing, said, “The surprise was that the collaborative approach works so well, that trying all the algorithms, coding them up and putting them together far exceeded our expectations.”

We’ve seen it work with open source software and multi-player online games. Now we have a very public example that in the digital world as well, many hands make light work.

Related posts: